Language Death and Revitalization

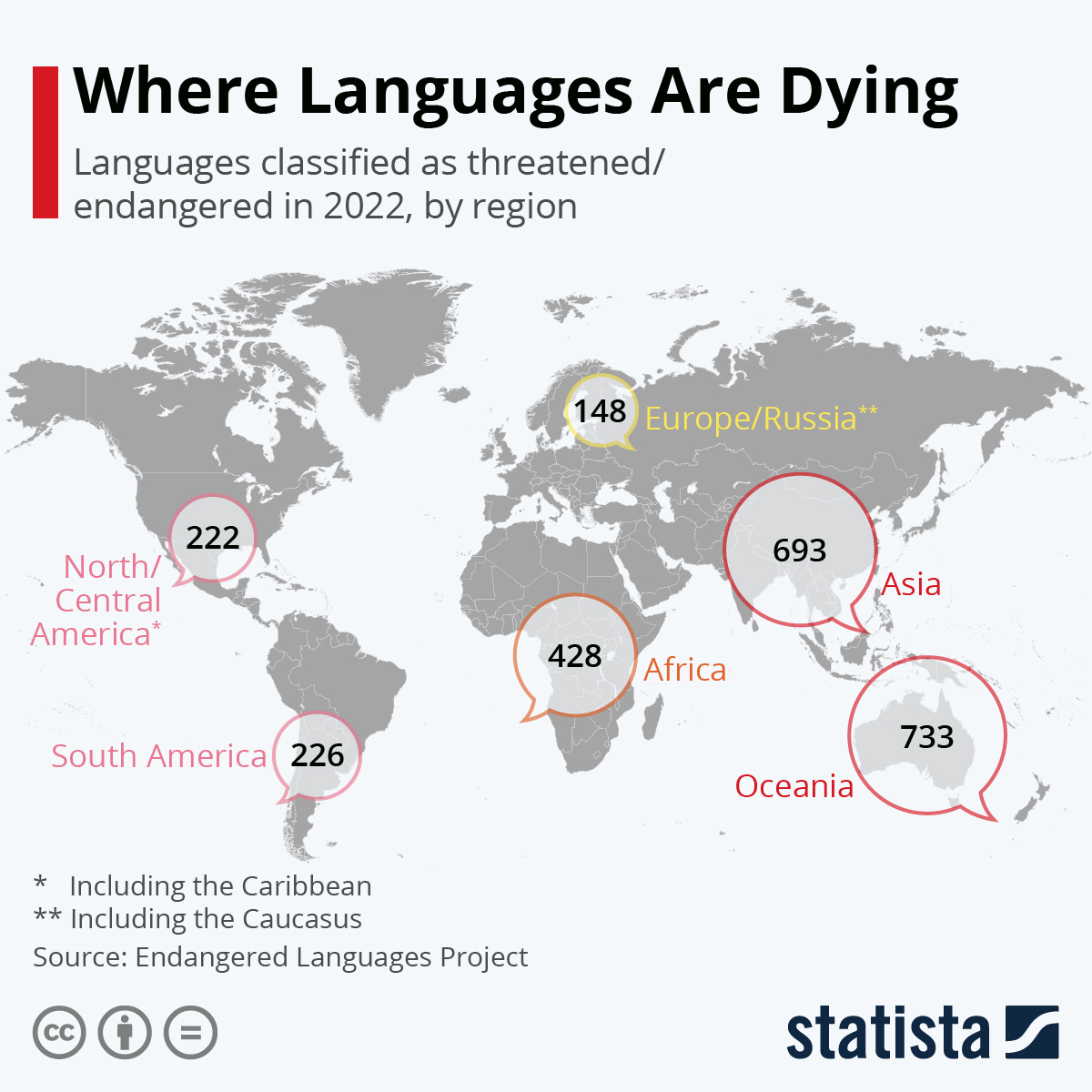

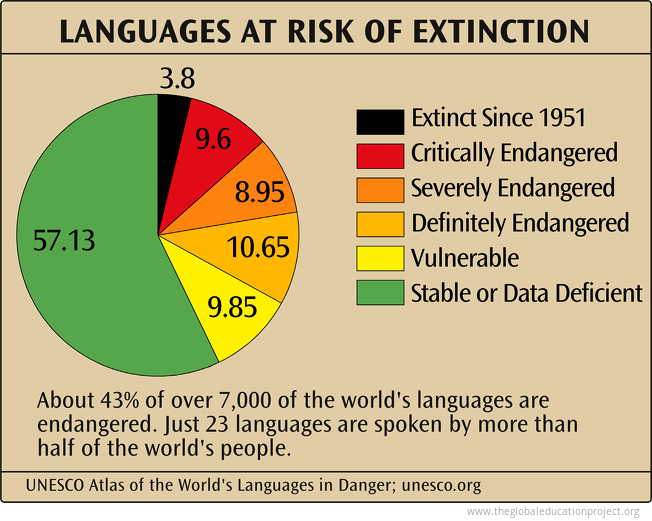

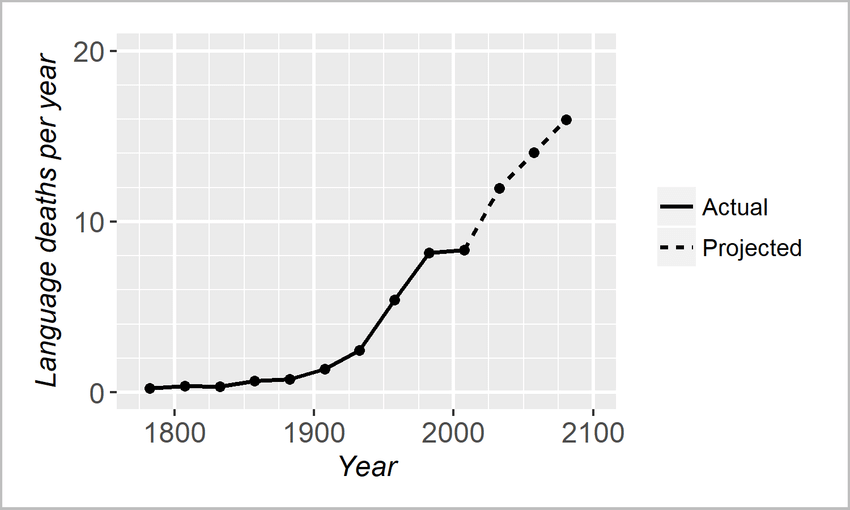

Every two weeks, a language dies. When a language dies, it means a people's tongue, way of life and perspective of speaking have gone – even unique writing systems. Of the 7,000 languages spoken today in our day and age, 50 to 90% of them may be extinct by the end of this century.

What Is Language Death?

Language death, sometimes referred to as language extinction, is when a mother tongue has no native speakers left. This can mainly happen due to the language not being passed down to one's child or not being widely taught. The standardisation of languages in a specific country also may contribute. with the extinction of indigenous languages. A language may start as "vulnerable", where it is spoken to a lesser degree than at its zenith. It then progresses to "definitely endangered" when children are not being taught the language of their parents, then "severely endangered" when only the elderly speak it. The last stage of a language before extinction is referred to as "critically endangered", when a small number of people can speak it – usually the elderly.

The final stage – extinction – comes when the last native speaker of a tongue dies. In 2010, the world lost Bo, an indigenous Andamanese language. In 1992, the world lost Ubykh through the death of Tevfik Esenç, a Northwestern Caucasian language. However, he collaborated with linguists to help document the language entirely; some of the documentation can be found here and here . These were not just the deaths of individuals, but the permanent silencing of entire linguistic traditions that had survived for millennia.

Why Do Languages Die?

The causes of language extinction are almost always man-made, as they usually involve some form of power imbalance or social stigmatisation. Whenever speakers of a minority language feel economical, social and/or political disadvantages, it compels them to abandon their native language in favour of the dominant language. As it offers better opportunities for them and their kin.

Colonisation has always been a driving force; that is the main reason why languages fall extinct. European colonial powers often enforced explicit policies to intentionally suppress a language. Whether through Eurocentric schools where they pushed their agenda onto the children or punishing them for speaking their native tongues, this has been a driving force of reducing linguistic diversity. The effects of these actions still reverberate way after colonisation had ended, such as with the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, where ethnic Tutsi people were massacred in the hundreds of thousands due to Hutu extremists. This was because of the German/Belgian colonists favouring the Tutsi over the Hutu because of their "tall stature" and because they believed they were closer to Europeans because of the aforementioned quality.

Globalisation and urbanisation also promote language shift through more subtle means. When people move from rural to urban areas in search of economic gain, they find themselves in a situation where the dominant language is necessary for educational, economic, and social advancement. Parents, who want the best for their children, find themselves deciding to raise their children in the language of prestige rather than the language of their heritage. This, in thousands of families, can be the death knell for a language in two or three generations.

Economic factors can also play a pretty substantial role; when a language cannot be used in commerce, it is bound to fall. It becomes confined to narrow domains and falls into obscurity, thus leading to extinction. It is imperative for it to be taught in institutions.

What Is Lost When a Language Dies?

The death of a language happens every 14-40 days, and it marks a stain. A stain that most likely cannot be bought back – the linguistic practices and special attributes of that tongue are gone. It is no longer natively spoken and most likely not even fluently spoken by anybody.

Because traditional ecological knowledge is so deeply ingrained in the language, it cannot be translated. The sophisticated taxonomy of local flora and fauna found in indigenous languages is frequently absent from mainstream languages. The Sami people of northern Scandinavia have a sophisticated vocabulary for various types of snow and ice that are unique to their culture of herding reindeer. Every word alludes to environmental factors that are necessary for surviving in the Arctic. The collective knowledge of the surroundings disappears along with a language.

Furthermore, there are different ways of understanding the world. An example is the Guugu Yimithirr language, which is an Aboriginal language spoken in Australia. In this language, instead of using 'left' and 'right', cardinal directions like 'north', 'south', 'east', and 'west' are used. This means that the people using this language are always orientated in their space and hence have better navigation skills. Studies have been conducted on the Guugu Yimithirr people and have proven the effect of language on the way people think and see the world.

From a perspective of pure linguistics, the death of a language reduces the diversity available for human language capacity. Rare grammatical features, unique sound systems and distinctive ways of structuring all contribute to our idea of what is possible in a human language. Each extinct language takes with it irreplaceable data for linguistic science.

Language Revitalization: Fighting Back

However, despite the grim statistics, numerous cases of language revitalisation from different parts of the world indicate that the death of languages is not inevitable, and people have found ways to give a new lease of life to dying and even dormant languages.

Closer to the present day, Māori in New Zealand have witnessed considerable revitalisation efforts in the past three decades. The establishment of "language nests" in which young children are taught in Māori, followed by primary and secondary education in Māori, has brought up a new generation of speakers. In addition, official status and media use, and the language's association with national identity, have contributed to this revitalisation. Although the status of Māori can be considered endangered, it has changed from a downward to an upward trend.

In the United Kingdom, Manx, a language on the Isle of Man, is slowly but surely being revived. In 1974, the last native speaker of Manx – Ned Maddrell – died. However, revival efforts have been able to raise the language back up from the grave. Today there are approximately 2,000 fluent speakers and a few children reportedly speaking Manx natively. Some institutions, such as the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, teach the Manx language to children.

Hebrew is a rare and well-known example of a language revival. Hebrew was for many centuries a liturgical and literary language but not a spoken language. Beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a concerted effort to revive the language, and today it is spoken by millions of native speakers. It is imperative to distinguish between the revitalisation of Hebrew and the fictitious State of Israel. Hebrew does not define the actions of "Israel" against the Palestinians of the Holy Land. I will always count myself as a person who is against "Israel" and the Zionist regime.

Strategies for Revitalization

There are several key elements that successful language revitalisation projects have in common. Perhaps the most important of these is community control over the revitalisation process. When these projects are driven by native speakers and community members, the language is much more likely to be a reflection of the needs, values, and cultural identity of the community and less likely to be driven by academic priorities.

Another key element of successful language revitalisation is the establishment of contexts in which the language is necessary rather than optional. Immersion schools and language nests provide a means of encouraging regular and meaningful language use by children and adults alike, which is essential for survival. Simply providing instructions for a language in the setting of a classroom is not likely to be sufficient in educating the child.

Technology has become an ever-increasing tool of language revitalisation. Tools such as digital dictionaries, language learning software such as Duolingo, and online documentation of extinct languages can aid in the revival of such extinct languages. For example, the Cherokee language has been immensely propped up by the amount of digital support for it, such as keyboard layouts, Unicode support and materials for education on the Web.

Last but not least, the learning of the language by future generations is essential to keep it far from extinct.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Language revitalisation is not without challenges. It requires much commitment along with funding. In addition, it requires teachers. However, it is not possible to have teachers without training, which requires funding. Moreover, it requires developing materials, which requires commitment. Finally, it requires developing enough speakers, which requires decades of commitment and hard work.

Additionally, economic issues are another factor that has continued to favour the use of the dominant languages. For instance, the language revitalisation efforts of the community recognise that the community is aware of the fact that, despite their commitment to language revitalisation, the parents of the children may still prefer to raise their children speaking English, Mandarin, Spanish, and other dominant languages so that they can have the best economic opportunities for their children.

Nonetheless, there are many examples of successful revitalisation efforts, and the act of successfully revitalising one's language is an act of self-determination.

Conclusion

The endeavour of minority languages dwindling makes us confront uncomfortable questions about diversity, power and our values as a world. We cannot stop languages from evolving and constantly changing. Change is the constant in language as in all other things. What we can and should do is to create a world in which communities make choices about their own language futures.

Essentially, the curbing of minority languages becoming extinct is bad. It is bad because it reduces linguistic diversity and shortens our mind of how capable and to what extent a language can be.